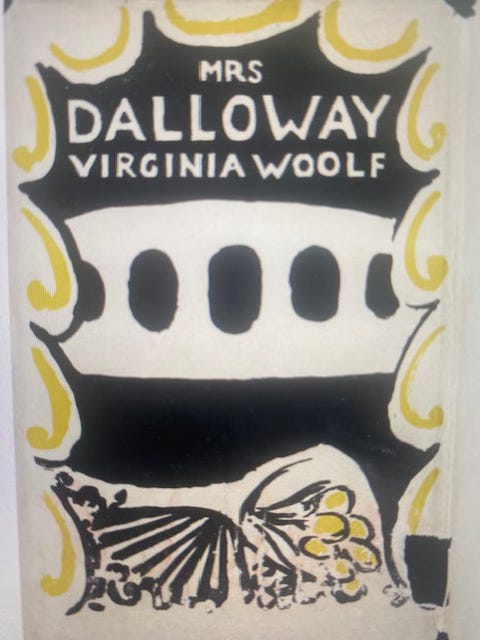

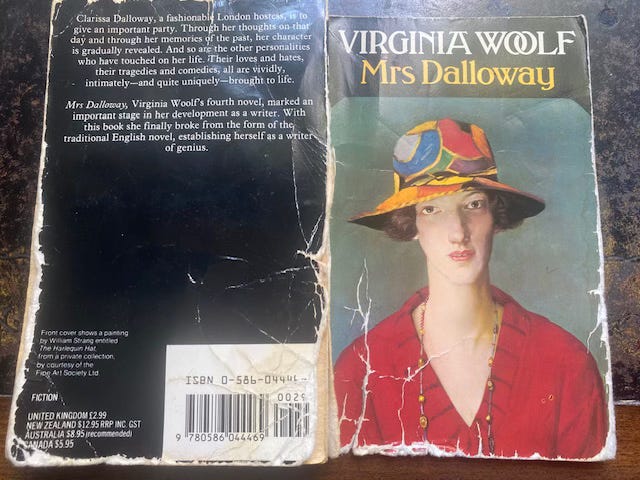

This week, a middle-aged British woman will celebrate her 100th birthday. Should that sound contradictory, the woman is question is Clarissa Dalloway, heroine of Virginia Woolf’s fourth and arguably greatest novel, published on 14th of May 1925. Mrs Dalloway was printed by Woolf’s own Hogarth Press, the dust jacket the work of her sister, Vanessa Bell. Bell renders the novel in a single image: flowers, a window, a balcony or reflected park bridge, the sense of a theatre curtain and/or framed life; its yellow, black and white conjuring something beautiful, fleeting, and mournful, despite the ostensible cheer.

Woolf and her husband had recently moved back to the central London and this is a London novel, in the way that The Waste Land (1922) is a London poem. Eliot’s work is a presence in the novel, not least embodied in Septimus, its “drowned sailor,” Clarissa’s troubled “double,” who hears birds sing in Greek (as Woolf herself had when lunatic). The novelist herself had set The Waste Land on the page for her press’s edition (no mean feat), and Eliot had visited the couple to intone the poem in a meta “He Do The Police in Different Voices” moment (his working title).

A year before, Woolf, then in her forties, had given a lecture, later published as the essay “Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown,” in which she declared culture to be “trembling on the verge of one of the great ages of English literature”. She wasn’t wrong, and Joyce too is present in Mrs Dalloway, Ulysses having been published in full in Paris in 1922. Both novels follow characters moving about bustling cityscapes on a single day, giving us their streams of consciousness. Writing in The Guardian in 2016, critic Elaine Showalter called for a “Dalloway Day” to be celebrated each year on a Wednesday in mid-June (when Dalloway takes her walk) to rival Dublin’s Bloomsday on the 16th of June. And various celebrations will take place this year. However, some of us celebrate Clarissa whenever we walk – alone, yet not alone - in the capital, carrying Mrs Dalloway as a ghost.

I first encountered Woolf’s novel aged 16 in what must have been a Braggian South Bank Show on the subject. (Melyvn Bragg’s 2014 In Our Time episode on it is also excellent – his testiness later revealed to be stress because he loves Mrs Dalloway so and yearns to do it justice.) A year later, aged 17, it was the text I chose to analyse for my Oxford Entrance Exam, the scene in which Septimus meets his Harley Street psychiatrist, juxtaposed with the episode in The Bell Jar (1963) in which an equally ghastly shrink patronises Esther Greenwood.

My father was a psychiatrist, growing up in the grounds of the asylum that his own psychiatrist father had charge of. The day before this fateful paper, I had spent long hours in an Accident and Emergency department, blue-lit there in an ambulance with my friend, Ben, the first time he tried to kill himself; an act he would finally succeed in after repeated efforts fifteen later. Psychiatry was so much the air I breathed that I don’t even remember seeing the irony in this.

I also didn’t yet realise that I too would be a lifelong depressive, rather than merely an unhappy child, followed by a Chekovian teen. However, I was already profoundly interested – enmeshed - in mental health. Even by the 1980s, one of my father’s most disturbed patient groups was a set of First World War veterans, now in their eighties and beyond, who had never been treated for Shell shock. This was also a time before Prozac became prescribed for depression, when my first boyfriend’s “nervy” mother had been rendered nervier still from electric shock treatment. Woolf’s openness in confronting psychiatric crisis - like Plath’s – felt radical, required; even where their fates hovered.

Culture, of course, has caught up with me, with Woolf. And no one who has suffered from mental illness can fail to be moved by her narrative, in which the mad and the miserable - and those who must be around the mad and the miserable - endeavour to stagger on. Septimus’s savage insanity is echoed in the fragmented flood of Mrs Dalloway’s depressed thoughts. Today, we might refer to this relationship as a “spectrum”.

None of this would matter a jot were Mrs Dalloway not also great literature - staggeringly brilliant, palpably first rate; one of the masterpieces of the literary age that Woolf felt culture on the verge of. I can see my former English lecturer self rolling her eyes and sighing that an art work isn’t to be judged by how profoundly we identify with it.

And, yet, for some of us this identification with Mrs Dalloway – and Mrs Dalloway herself - is also extremely precious.