Forgive me not ‘stacking yet this week. Feeling a tad flu-deranged. (So much for last week’s attempt to allay bolster immunity against Trump.) I traditionally used to succumb at the beginning of December during Peak Party Week. However, party week has dragged forward and with it my lurgy.

I’ve just filed Monday’s Mail column on beauty as germ warfare. Of course, it features my beloved, bug-offing Dr Bronner's Organic Lavender Hand Hygiene Spray (now £4.60, planetorganic.com). Otherwise, my discovery of this malady for those obliged to stagger on has been Revolution Pout Bomb Plumping Gloss in Jelly Berry Mauve (now £4.79, superdrug.com). Stay with me here. The shade distracts from the redness of your nose / eyes, while its tingly peptide, hyaluronic acid, vitamin E and jojoba oil shine prevents lips chapping.

I’ve also been putting This Works Perfect Heels Rescue Balm (now £14.40, johnlewis.com) on my sore nose. Heaven! While Trinny London BFF De-Stress (£39, trinnylondon.com) is a skincare / slap hybrid that really does magically mitigate against a knackered, unslept complexion. Still, if you can just go to bed, go to bed.

For lunch I forced myself to consume marmalade on toast because smell, tang, crunch!

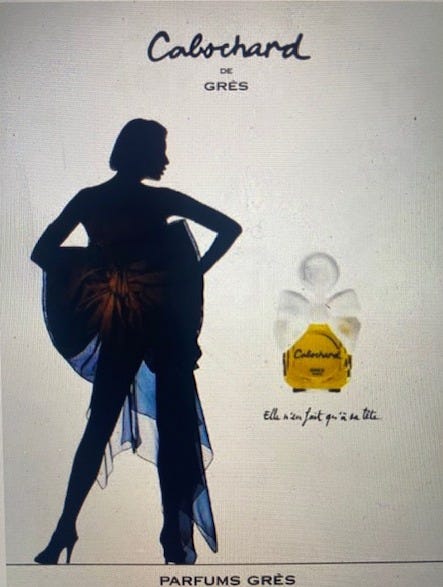

Then, I drenched my body and bed in Cabochard by Grès (£14, Debenhams.com). Cabochard, meaning “stubborn” or “headstrong”, is a seductive leather chypre – or earthy, oakmossy – concoction, created in 1959 by Bernard Chant, composer of Clinique’s Aromatics Elixir (released in 1971, the year I was born).

After the verdant orange of its opening - suffused with aldehyde (sparkling) aspects - and spiced middle notes, Cabochard gives way to a cloud of leather, smoke and powder. Reformulated in 2019, it can now be found for less than 20 quid for a whacking 100ml. Some find it a heart-wrenching ghost of its former self. However, there’s enough of the ghost to haunt. Sported out and about, and you will be besieged by compliments. Worn feverish between the sheets, and you will feel almost human.

Yule has traditionally been when perfume sales ring through the nation’s tills. For it is now - with the scent of pine, chestnuts, oranges, incense, wood smoke and plum pudding in the air - that 50 per cent of fragrance purchases are made. If anything, this tendency is on the rise. The Perfume Shop alone sold 1.8million flacons between November 28 and December 24 2022 - the greatest festive trading performance in its 30-year history - despite Royal Mail strikes and a cold snap keeping shoppers indoors.

I must start turning my mind to this December’s olfactory recs. Meanwhile, I unearthed this article from The Times, in December 2006, pegged to the film Perfume. You may recall the novel’s second paragraph:

In the period of which we speak [pre-Revolutionary France], there reigned in the cities a stench barely conceivable to us modern men and women. The streets stank of manure, the courtyards of urine, the stairwells stank of mouldering wood and rat droppings, the kitchens of spoiled cabbage and mutton fat; the unaired parlours stank of stale dust, the bedrooms of greasy sheets, damp featherbeds, and the pungently sweet aroma of chamber pots. The stench of sulfur rose from the chimneys, the stench of caustic lyes from the tanneries, and from the slaughterhouses came the stench of congealed blood. People stank of sweat and unwashed clothes; from their mouths came the stench of rotting teeth, from their bellies that of onions, and from their bodies, if they were no longer very young, came the stench of rancid cheese and sour milk and tumorous disease. The rivers stank, the marketplaces stank, the churches stank, it stank beneath the bridges and in the palaces. The peasant stank as did the priest, the apprentice as did his master's wife, the whole of the aristocracy stank, even the king himself stank, stank like a rank lion, and the queen like an old goat, summer and winter. For in the eighteenth century there was nothing to hinder bacteria busy at decomposition, and so there was no human activity, either constructive or destructive, no manifestation of germinating or decaying life that was not accompanied by stench.

Three months later, my piece won the literary prize at the 2006 Jasmine Awards for perfume writing, which was rather nice. Fifteen years on, not much has changed. I’m living with a different boyfriend, but still following my nose. And I would still rather wear Tabac Blond (1919) or Bel Ami (1986) than some banal, passing flanker. I hope this (slightly updated) serves as a substitute for actual, non-snotty thought.

Picking up the scent by Hannah Betts

Recently I found myself scurrying towards breakfast through the avenues of Mayfair. It was not yet 9am, the streets apparently empty, and yet crowded with repulsively over-ripe olfactory encounters. First came morning aromas: coffee, bread and stewing meat, ready for noon’s business lunches. Next, great washes of soap suds endeavouring, unsuccessfully, to erase lingering traces of nocturnal vomit.

The scent of hot hair leached from salons administering blow-dries. A man - most definitely a man - who had taken my path moments before, left an acrid stench of armpit in his wake. An elderly chihuahua on its morning constitutional had pockmarked the pavement with robustly undiluted urine; while some gigantic police mount had left a still more emphatic trail. It was as much as I could do to keep walking, near felled by stomach-churning sensory overload.

Lately, this sort of thing happens to me a good deal: fish markets are an impossibility, locker rooms yeastily unpalatable, public transport a spermy abomination. A lifetime’s obsession with smell, followed by four years writing about perfume as the Times Magazine’s beauty columnist, has rendered me a nasal neurotic, equipped to sniff out a foreign body at ten paces. Although I can’t compete with Jean-Baptiste Grenouille, the antihero of Patrick Suskind’s novel Perfume, which is released in film guise on Boxing Day. Grenouille has a nose so exquisitely developed he can smell glass; and he spends his life in pre-Revolutionary France in pursuit of the ultimate scent - the essence of 25 virgins.

The sanitised streets of 21st-century Mayfair have nothing to compete with the stews of 18th-century Paris. But still, with the exception of those poor individuals with anosmia, I am living proof that enhancing your capacity to smell may be as simple as activating your nose, and switching on this most dormant and neglected of senses.

The mythical sixth incarnation apart, smell has long been considered our most enigmatic sense, as the science behind our ability to identify thousands of different odours remained largely a mystery. All this changed in 2004 when Linda Buck and Richard Axel, of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Maryland, were awarded a Nobel prize for their pioneering work in the field.

Experimenting on mice and human cells, the pair discovered a family of 1,000 genes responsible for an equal number of olfactory receptor sites that detect inhaled molecules. Each of these receptors is specialised and can detect a number of related odours, information they then convey to the brain. Here communication from several olfactory centres is brought together, forming a pattern that can be recalled at a later stage. This explains how you can still remember the scent of spent fireworks in June, or the smell of your grandmother’s silk scarf long after she is gone.

Scientifically speaking, then, all senses of smell are created equal. But, if so, why is it that a talent for fragrance can appear to be inherited, and the offspring of so many perfumers follow them into the field? Names that are distinguished in one era regularly recur in the next. No one can speak with more authority on this subject than Jean-Paul Guerlain, the fifth generation of the French perfume house, and its fourth-generation nose. Of these four, it is Jean-Paul and his grandfather, Jacques, who have been its pre-eminent geniuses: the former responsible for Vetiver (1959), Derby (1985), and Samsara (1989), the latter the creator of the immortal L’Heure Bleue (1912), Mitsouko (1919) and Shalimar (1921/5).

For Guerlain, olfactory talent is a matter of nurture rather than nature. “Everybody can smell,” he maintains. “It is merely a matter of work. When you smell different raw materials day in, day out over many years you will come to recognise them. The most difficult area is creativity, how to work with the imagination. Here the power of the family is important, not least when you are born into one where the talk is mainly of perfumes. My great opportunity was that I was only 16 when I started to work with my grandfather. Our job is wonderful, but it needs a tremendous amount of patience and work.”

We may not have the guiding influence of a Jacques Guerlain in our lives, but is still possible to smarten up your olfactory act. Moreover, Christmas presents the perfect opportunity to begin developing your nasal capabilities, when the scent of pine, chestnuts, oranges, incense, wood smoke and plum pudding are heavy in the air, and 50 per cent of all perfume sales ring through the nation’s tills.

Fragrance is the consummate marriage of art and science, and it pays to approach the subject with the seriousness with which you indulge other sources of sensory and aesthetic stimulation, such as music, literature, wine and food.

The three principal genres are: floral, oriental (musky, spicy and exotic), and chypre (citrus top notes, floral heart, mossy underbelly). There can be some crossover between these camps: someone who relishes florals may dally with the more ethereal orientals; an oriental enthusiast may flirt with the occasional lusty chypre. However, floral types tend to turn up their noses at chypre lovers and vice versa.

In developing an olfactory palette, you rapidly come to appreciate that tastes collide. My own penchant for the mossier, leatherier, more resinous chypres such as Caron’s Tabac Blond chimes with my predilections in tea, wine, food and scotch, where a smoky lapsang or peaty Islay malt will always be more desirable than pastry or pudding wine.

I have also been informed that I look and dress chypre: brunette, somewhat arch, with echoes of the Forties when so many classic chypres were composed. An eminent perfumer once nodded insouciantly in my direction: “But of course you are chypre. You are a feminist, you relish sex, you exploit your feminine wiles. What is floral here?” Gallic nerve, but there is something in his argument. Meanwhile, the blossoms so loved by others induce rage and claustrophobia in me; the orientals adored by my sisters, mordant disgust.

The notion of perfume as personality may sound fanciful, but so much in fragrance comes down to emotional intelligence, a looking inside oneself. There may be rules, families, genres, but ultimately scent is subjective. You may learn to recognise materials, but your fixations will derive from formative, typically childhood experiences, from longing, memory and desire. So Jean-Charles de Castelbajac’s eponymous fragrance evokes the sweet-almond glue of the schoolroom; Mugler’s Angel the fairground’s sugar and sawdust. Sometimes scent can restore a memory lost. Comme des Garcons No 3 made me realise that my grandparents possessed a fig tree; my phobia of ladybirds is attributable to the stink they left on my limbs during the drought of 1976.

But, be warned, my new-found powers are the bane of the lives of those close to me. My boyfriend refers to me as “The Child Catcher” after the brilliantined menace in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. And where he lives in fear of my ability to sniff out secretly-quaffed tipples and nicotine-dank fingers, so he has won bar-room bets with my ability to distinguish brands of single malt.

I am fluent in the varieties of bad breath: the clammy reek of sour wine, gaseous belch of vacant stomach, or stench of oral abscess. Believe me when I tell you that the world is full of people who need to floss. And, then, there are the nasal passages’ unexpected assailants: horse excrement, a rat’s nest, the powdered interior of a handbag, or the cool, silver scent of coins.

Three times now I have recognised the smell of death, once, grotesquely, before the person in question knew. Such tales propel my medical parents into anecdote about the ways in which smell can act as illness’s alarum. Diabetes and liver failure are cloyingly sweet, urinary tract infections fishy, candida suitably yeasty or cheesy. Suppurating gangrene emits a heinous rotting odour, perversely relished by some.

Instead, I would rather enjoy the ultimate perfume, the aromatic allure of one’s beloved (believed to be a sign of compatibly dissimilar genes), laced with a lingering leather or moss. Jean-Paul Guerlain believes fragrance can be inspired only by romantic passion: “Always a woman, all my life. I do not think you are able to create perfume if you are not in love.” On receiving his tribute, Decia de Pauw, the muse for whom he composed Samsara exclaimed: “This is the greatest gift a man ever gave a woman”. His reply: “I was but the stone mason, you the architect.”

This is what we will all be searching for this Christmas: a scent that augments someone we adore, on whom it becomes greater than the sum of its parts. Get it right, and a fragrance purchase made today could become the most intimate and powerful means a loved one has of expressing themselves.