By Hannah Betts

It’s #tiaratime here in London this spring. At Buck House, The King’s Gallery Edwardians show boasts three absolute humdingers: Queen Alexandra’s Kokoshnik (1888), the Girls of Great Britain and Ireland (1893), and the Delhi Durbar (1911). Over at the V&A’s Cartier extravaganza, there’s a king’s ransom of them: from the moodily-lit Manchester Tiara (1903) at its opening, via various royal numbers, to the whole room full of them at its end. Well might its security guards look edgy.

There will be those who dismiss so many dazzling diadems as fairy-tale whimsy. However, monarchy is built on such fairy tales. After all, as an inscription on the wall of the V&A exhibition states, the greatest number of tiaras ever commissioned was created by Cartier for the Coronation of May 1937. The V&A curators don’t labour the point; they don’t have to. One hears the implicit message: less than six months after the abdication of Edward VIII in December 1936. If flighty David had put the throne in jeopardy, then the British aristocracy would rally round to prop it up again - head-first, coroneted, bauble by coruscating bauble.

Back in Tiara Town, it is impossible not to play the game “Which creation would I lay claim to, given the opportunity?” I ‘fessed up as much to my friend, Caroline de Guitaut, Deputy Surveyor of The King's Works of Art, who happened to be standing alongside the Kokoshnik and Girls of Great Britain & Ireland when Terence and I attended. Caroline and I have enjoyed many happy hours gazing at royal bling together, and she’s the author of 2022’s Diamonds: A Jubilee Celebration, a celebration of 21 of the most significant diamond confections sported by the Royal Family for over 200 years (a jewel in itself - do seek it out).

The Delhi D leaves me cold, despite George V referring to it as “May’s best tiara”. Queen Camilla wears it well, but its lofty circlet of lyres and S-scrolls is too frou frou for me. The Girls of GB and Ireland feels like the national tiara, so familiar is its foliate form from generations of banknotes.

Nevertheless, from the King’s Gallery, I would have to pick the Kokoshnik, each bar pavé-set with brilliant cut diamonds, embedded in white and yellow gold. There’s a simplicity to it – a lavish simplicity, to be sure, but a simplicity nonetheless; exclamation-mark beams erupting from the top of the head as if one is not merely crowned, but a goddess.

From the Cartier show, it would have to be the Olive Wreath Tiara (1907), commissioned for the nuptials of Princess Marie Bonaparte and Prince George of Greece and Denmark, its neoclassical style alluding to the bride’s heritage, as Napoleon’s great grandniece, with olive leaves no less befitting a Greek bride. Would I tinker with the great, pear-shaped diamond at its centre, swapping it for a colossal star? Reader, I might. Would I also trade its eleven, big, cushion-shaped diamonds for emerald “olives” from time to time? Guilty as charged.

That said, I wouldn’t be too unhappy if in receipt of the Cartier Pearl Kokoshnik (1908)….

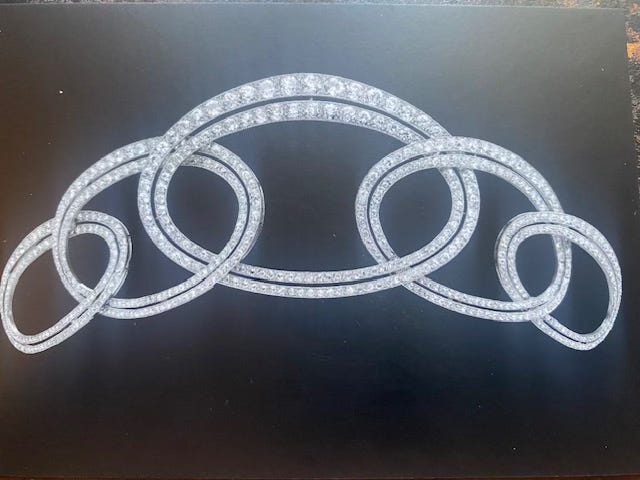

or, indeed, the large, linked, avant-garde number also of 1908, sold to Ned Stotesbury.

Wait, I appear to have a Cartier tiara era (1907-8), just as I harbour a gentlemen’s Omega watch era (1938-9), as sourced from my beloved Antique Watch Co at 19 Clerkenwell Road, where I also purchased my vintage Cartier tank.

Back to diadems, I harbour no Disney princess aspirations; scorning even that entry-level qualifier, the wedding dress. However, I am a lifelong tiara obsessive, owning several low-rent versions, sported at parties or aboard a gondola at the Venice Film Festival. For the purposes of my so-called job, I was once crowned with a 178 carat Graff incarnation (see below). I like to think that almost three decades in journalism has rendered me largely unimpressionable. Not so much. The transformation was profound: for the first and only time in my life, I looked beautiful.

Tiaras are ageless – Queen Camilla wears one particularly brilliantly. And they’re so winningly practical, the architecture of a coronet invariably including the ability to wear it as a necklace, or with a stone convertible into ring, or brooch (with Cartier’s, diminutive screwdriver kits lie beneath the box’s liftable velvet false floors). Were I to lay claim to a proper one – the Windsors’ Kokoshnik, Cartier’s Olive Wreath, or Barbara Hutton’s emerald Cartier showstopper, say - I would never be out of it, whether pelting down Piccadilly, or disporting myself in the bath, à la Snowden’s portrait of Princess Margaret.